What makes Ubuntu Ubuntu? Linux is available in the form of a number of so-called distributions, from the well-known Ubuntu to specialists such as Slax, to insider tips such as BunsenLabs. We'll show you how distributions differ, what derivatives and flavors are all about.

GNU / Linux

Often the term Linux is used simply, like: "This is how you secure Linux." This is not entirely correct for several reasons. It starts with the fact that such a manual would have to look completely different for Debian and Ubuntu - but more on that later. And even to refer to both of them as Linuxe is already annoying some enthusiasts: Strictly speaking, it should be called GNU / Linux. Linux is the kernel initiated and maintained by Linus Torvalds, which in most distributions ensures that the PC hardware becomes a usable something at all. The kernel is a bit like a workbench: You cannot work without a workbench as a basis - but neither without tools..

And that's where the GNU comes in. GNU stands for GNU's not Unix and is an operating system with origins in 1984 - with a kernel that has not yet been completed. Instead, Linux is used as the core. So when people speak of "Linux" today, they usually mean the combination of the Linux kernel and GNU tools. GNU / Linux, in the following only Linux, is the basis for Ubuntu, Debian, OpenSuse, BunsenLabs and the many hundreds of other distributions.

The distribution

The most noticeable feature of a distribution is already clear very quickly: Pure GNU / Linux only offers a terminal, no graphical environment. So you could combine GNU Utilities, Linux kernel and a desktop such as Gnome and you would have your own distribution. Well, of course you would actually have to make them publicly available and distribute them, in other words distribute them - hence the name..

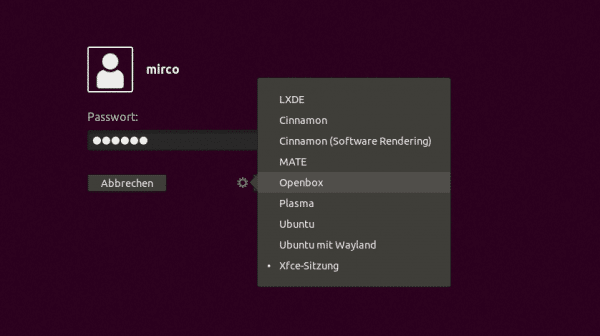

Desktop environments can also be switched within a distribution.

Desktop environments can also be switched within a distribution. A desktop environment is much more than "just" a pure graphical user interface. Most desktops also have a number of tools of their own, programmed in such a way that they fit in well with the system and can share many resources.

In general, tools are another characteristic of a distribution. Sometimes there are dozens of pre-installed tools to give the user a real complete system. Sometimes there is only the bare minimum so that users don't have to deal with ballast. A question of philosophy..

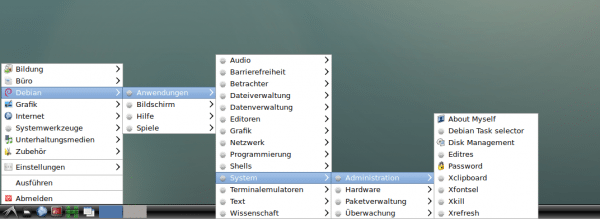

Debian makes it clear: Debian tools have their own menu.

Debian makes it clear: Debian tools have their own menu.

The same applies to the default settings of the tools, the kernel, the desktop environment and generally all adjustable aspects of the system. For example, one distribution just wants to make it as easy as possible for the average consumer, the next one puts more emphasis on security and requires the user to set up more effort accordingly.

This also applies to what is perhaps the most important point when it comes to maintaining the system: updates. Of course, the update policy is again a philosophical question: With fixed releases, for example, you get a new version once a year - and you have to upgrade accordingly. With rolling releases, however, you only install once and the system is kept up-to-date for years without you having to intervene. With Ubuntu, for example, there are new versions at fixed intervals, which are also provided with updates such as security patches beyond this interval. The so-called LTS (Long Term Support) versions of Ubuntu remain up to date for a full 60 months.

And who decides all of this? The project behind the distribution, of course. And that is another factor that should not be underestimated. Ubuntu, for example, is largely developed or published by the Canonical company. The advantage here should be: As a company, you are very fixated on end users, on easy handling, polished surfaces and general simplicity. But such a commercial background also has disadvantages: For example, Canonical built Amazon advertising into the desktop at some point, which the Ubuntu community didn't find funny at all. As with operating systems from Apple or Microsoft, decisions are not always made in the interests of the user. Debian, on the other hand, is maintained by a community and is aimed much more at professional or more experienced users.You would never have to fear things like advertising here - but just finding the right download file is pretty terrible for laypeople ...

Derivatives and Flavors

Ubuntu and Debian are actually completely on the same wavelength: Ubuntu simply takes Debian as its basis and then changes the standard desktop, tools, settings, update policy and so on. Ubuntu is a derivative of Debian. That's the beauty of open source software: Anyone can take such software, change it according to licensing rules and distribute it with a new design, a new logo and a new name. Ubuntu is so successful that there are hundreds of derivatives of Ubuntu itself - Debian's grandchildren, so to speak.

Of course, each derivative is in turn its own distribution. Basically, it's just about making your work easier. A project like Debian can't be done with three people, but a Debian-based distribution can. Some users push the customization of their own system so far that they basically run a distribution for themselves.

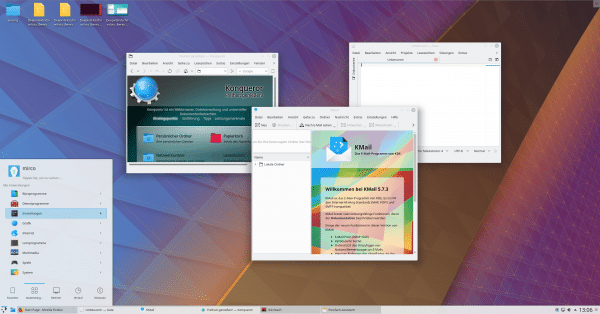

Ubuntu with KDE desktop and tools: Available as Flavor Kubuntu.

Ubuntu with KDE desktop and tools: Available as Flavor Kubuntu. So Debian is quasi an original distri and Ubuntu is a derivative distri derived from it - but what are Kubuntu, Lubuntu etc. then? There are many distris with different desktop environments. Sometimes the desktops are simply available as a selection during the installation, but sometimes sub-projects are also maintained, which then offer Ubuntu not with Gnome, but, for example, KDE (Kubuntu) or LXDE (Lubuntu). Such partially independent versions are often called flavors, but that is not a fixed term. In some projects these flavors can also be seen in other facets, for example light versions with less standard equipment or huge "DVD versions" that contain half the Internet. Such flavors are not their own distris.

Distri families

Basically it is now clear what distribution, derivative and flavor mean. For an overview, however, it is still interesting to take a look at the big picture. In addition to Debian, there are other independent distributions that are not derivatives - but serve as the basis for derivatives. The bases for these distri families are mainly Debian, Arch Linux, Red Hat and Ubuntu, even if Ubuntu is a Debian derivative as I said. The best-known derivatives include Linux Mint and elementary (Ubuntu), Kali Linux and Raspbian (Debian), Manjaro and Antergos (Arch) and the Red Hat derivatives Fedora and CentOS.

In addition, there are all sorts of independent distributions without a large number of successors, for example Slackware, Gentoo, OpenSuse, Puppy Linux or the tiny Tiny Core Linux. Wikipedia has wonderful graphic overviews of families and derivatives - it really opens your eyes!

By the way: The big advantage of this family knowledge: Switching within a family is usually much easier. From Ubuntu to Mint is a tiny step - from Ubuntu to CentOS a free fall from an airplane.

Linux Mint as a Debian / Ubuntu derivative is very easy to learn for Ubuntu users.

Linux Mint as a Debian / Ubuntu derivative is very easy to learn for Ubuntu users. Differences in detail

Finally, a small example should show that distris differ not only in terms of size, in things like desktop or update policy. Take Ubuntu and Debian and two details that make enormous differences, especially for normal users:

- Package selection: Debian relies on stability, which is why the package manager often installs completely outdated versions of programs such as Gimp. Ubuntu would rather provide its users with all the latest features and deliver correspondingly more up-to-date versions via the package management.

- Root rights: If you want to work with root rights under Debian, the standard way is to switch to the "root" user via "su" - and then back again when the work is done. Under Ubuntu, on the other hand, the user is granted temporary root rights for this call via "sudo" before a command - an explicit termination of the root session is not required. Here, too, the reason lies in the fact that Debian addresses expert users, whereas Ubuntu addresses the average consumer.

Now you know what makes a distri and you can look around for a suitable variant - a good starting point for this is always the page http://distrowatch.com . Another tip for Linux beginners: The sheer size of a project is an advantage that should not be underestimated!